Inspired-Search Interview with Elle Dings, the Vice President Supply Chain at Lumileds :“ We supply mainly standard products in the illumination and conventional automotive markets, and customization in our other two markets. Even so, the supply chains are very different. In the specialty market we have dedicated production lines that can only make between five and ten different products. “

Lumileds, a manufacturer of various types of lighting solutions, is active with two different types of technology in three different segments. Each segment has its own unique supply chain characteristics, but one thing they all have in common is a complex network. In the case of LED technology, the lengthy and uncertain production process further complicates the situation. Elle Dings, VP Supply Chain, is responsible for aligning supply and demand, despite the long lead times and unpredictability.

A couple of years after graduating with a Master in Engineering Management from TU/e in the Dutch city of Eindhoven, Dings joined Philips Lighting and received black belt training. As a consultant, she learned a lot thanks to seeing every facet of the supply chain and after a few years she became keen to shoulder operational responsibility herself. Her wish came true when she accepted a role in Malaysia to improve the supply chain maturity at one of the Philips Lumileds factories. “The lead times in the semiconductor industry call for exceptionally good planning. We developed our own tooling for that due to the lack of standard software that suited our processes,” she says.

Her achievements didn’t go unnoticed. Around the time that Lumileds split off from Philips, in 2012, Dings got the opportunity to move to Silicon Valley and set up the entire S&OP process for the company’s LED business units in San Jose. She subsequently became Director S&OP and headed up those processes for five years, until she eventually decided to return to the Netherlands for personal reasons. As it happened, her boss decided to step down at around the same time. “He asked me to become VP Supply Chain for the whole of Lumileds, which meant taking on the lighting business in addition to the LED business. Since the majority of the factories for the conventional lighting products are in Europe, that was definitely doable from the Netherlands. To be honest, it doesn’t really matter where I’m based because I have global responsibility, but Europe is handy with respect to the various time zones.”’

How would you describe Lumileds’ market?

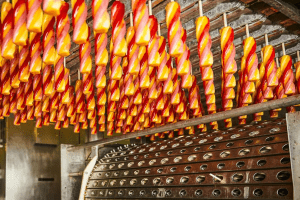

“We produce lighting solutions for several market segments. The first market segment is Specialty, which includes things like the flash on smartphone cameras. The second segment is Illumination, which is pretty much all generic LED lighting. Those products are the reason that Philips divested us – they are mainly standard products and there is intense competition, especially on price. We manufacture them ourselves but we also outsource some of our production to Chinese companies. Our third segment is the Automotive business unit, which is split into LED lighting and conventional lighting, although that is shrinking all the time due to the shift from conventional lighting to LEDs for new cars. The aftersales market compensates for this decline.”

And what about your supply chain?

“We supply mainly standard products in the illumination and conventional automotive markets, and customization in our other two markets. Even so, the supply chains are very different. In the specialty market we have dedicated production lines that can only make between five and ten different products. Our processes are very tightly integrated with those of our customers; we have full insight into our customers’ forecasts. While we also offer customization for the automotive LEDs market, there is a lot more variation in terms of products and customers. In that case, a single LED production line is used for hundreds of different customers and thousands of different products.”

What falls within your scope of responsibility?

“My supply chain team is responsible for demand planning, S&OP, operational supply planning, factory planning, material planning, distribution, warehousing, and supply chain improvement projects and systems. So the factories aren’t within my scope of responsibility but we do plan the loading at the factories. And it’s the same for procurement; we don’t do our own procurement, but we do dictate what needs to be purchased. Within our company, the general principle is that Supply Chain runs the business. In the past the factories themselves had a lot of autonomy to decide what they would produce, but that simply wouldn’t work nowadays. The inventories would impact far too heavily on our cash flow.”

What causes the uncertainty on the supply side?

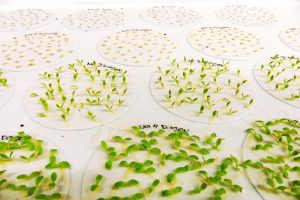

“The production of LED lighting entails a lot of factors that prevent 100% constant output; that’s inherent to our production process. Making a wafer is a chemical process, for example, so there can be differences in the light produced by an LED. It doesn’t matter how good your quality programmes are, you simply can’t avoid that. It’s just a factor that we have to deal with in the supply chain. We need optimization programmes for bin matching. The challenge is to translate the demand into the right number of bins for the various stages of your production process. Downtime has to be constantly monitored and production adjusted to minimize it. Another aspect I have to keep a close eye on is the long-term demand trend because the lead times for new machines are extremely long. If the demand increases, we can’t scale up our production at the drop of a hat. But when is it the right time to invest in extra production capacity?”

How do you manage your organization’s four supply chains?

“I’ve divided my team into four groups, one for each of our markets: Specialty, Illumination, Automotive LED and Automotive Conventional Lighting. The LED and conventional supply chains are so different from one another that they can hardly make any use of shared processes. In the case of the automotive market, we combine our logistics processes by merging the two segments.

At an organizational level, we work according to the same principles everywhere in the supply chain. And it’s important to me that the four teams learn from one another, so we share best practices. Although those best practices can hardly ever be copied directly to a different market, they can often be adapted to fit.”

What exactly are those shared supply chain principles?

“The most important one is that we’re forever looking for ways to optimize. That’s partly due to my background as a black belt, and due to my experience in far-reaching process automation and the use of data to improve decision-making, of course. We use SAP/IBP for demand planning and the first part of S&OP. However, SAP is a standard tool. It’s fine if there’s a one-to-one relationship between your production process and the end product that you’re starting up, but if there are one-to-many relationships at the end of your production process, then the SAP/IBP support doesn’t go far enough. That’s why we work with tooling that we’ve developed ourselves. It enables us to model and optimize our own processes just as we want. One of our goals from now on is to develop even better tooling for demand forecasting because our supply chains are increasingly demand-driven. Our company is traditionally very good at the operational aspect, but we need to become more agile when it comes to rapidly adapting to changing customer demand.”

What’s your role in the management team?

“As I already mentioned, Supply Chain runs the business at our company. Ultimately all of an organization’s problems – whether they originate in Sales, Finance or Engineering – end up in the supply chain. I’m a big fan of collaboration. To be a good supply chain manager, you need to be able to see things from the other person’s perspective. I work in very close partnership with Finance because the supply chain risks are financial ones, and likewise I have a very intensive relationship with Operations and Sales. There’s a member of my team in all the factories’ management teams (MTs). I generally only work with Engineering if there are any issues. If we are at risk of running into any problems, I immediately tell the relevant people. I find that if I explain clearly what kind of help I need, I get it because everyone in this company is aware of the importance of Supply Chain in relation to our customers. It’s no longer necessary to put our discipline on the map.”