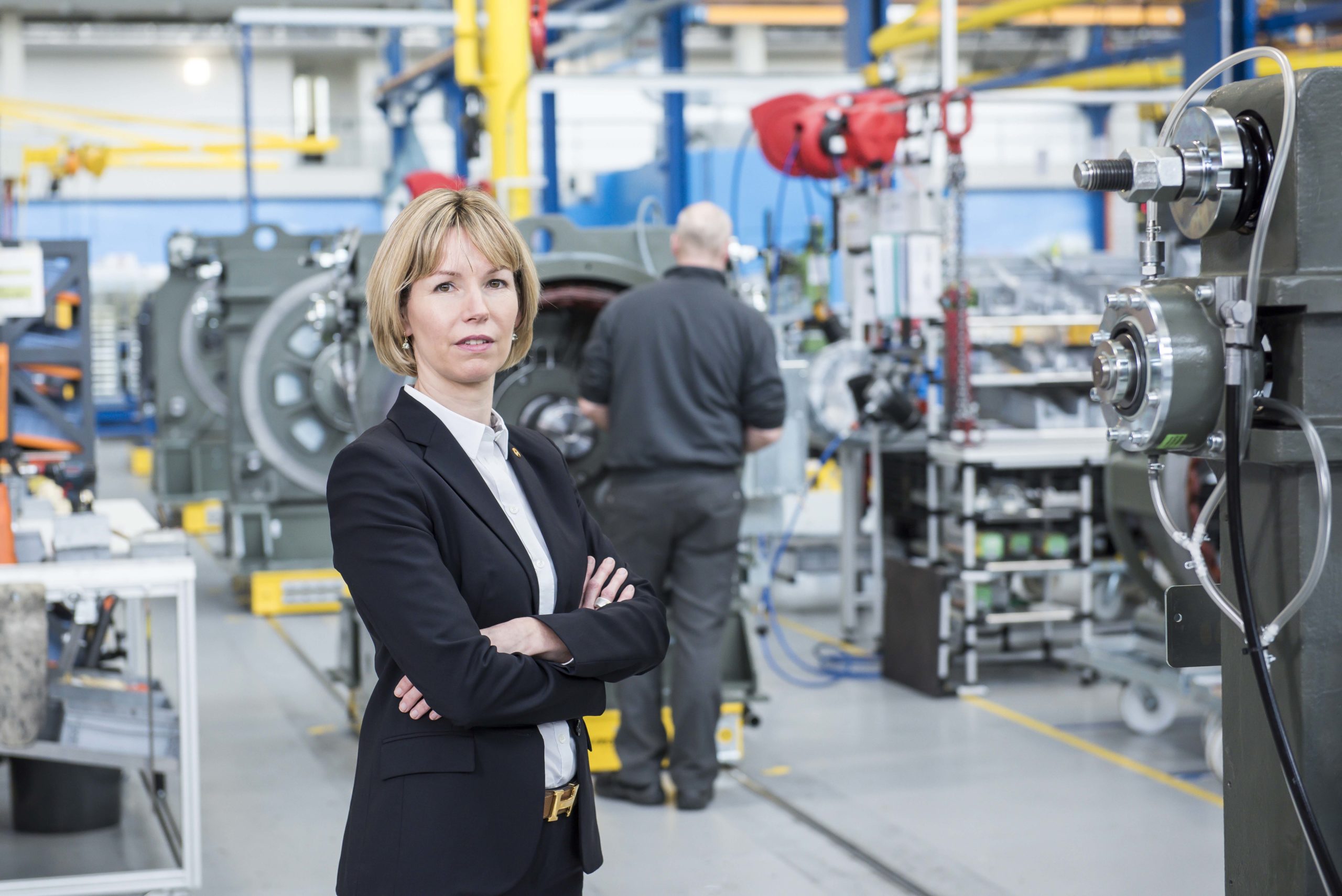

Talented and ambitious, Sabine Simeon-Aissaoui was in full flight when an unsuccessful project, which she initiated in China, knocked her confidence. It gave her time to regroup, think, and come back with renewed energy and determination. After a short spell working for a supplier in Singapore she returned to the Swiss Schindler Group in 2014 and transformed its European Supply Chain. This led to her receiving the APICS Award for Excellence–supplychain leader, an award that honors extraordinary team and organizational leadership, mentoring of fellow professionals and contributions that advance the supply chain industry as a whole. With an operational mindset Simeon-Aissaoui prefers ‘to do’ than ‘to talk’ but enthusiastically shares her experiences in order to inspire others.

The decision by the Schindler Group, head- quartered in Switzerland, to switch its focus from manufacturer to service provider in 2000 was not all plain sailing. A decade later it still faced challenges, including maintaining competitiveness in material cost.

Sabine Simeon-Aissaoui was appointed head of supply chain Europe in 2014 and spent two and half years reinventing the supply chain and cut- ting complexity. Today the company’s Swiss engineered elevators, escalators and moving walkways move 1 billion people per day and it is at the forefront of optimizing urban transportation and facilitating the development of smart cities. Founded in 1874 in Lucerne, the company employs over 60,000 people in more than 100 countries. As head of supply chain Europe, Simeon-Ais- saoui runs an organization of 1200 people with 13 direct reports, four manufacturing plants and four distribution centres. Her European supply chain incorporates planning, strategic sourcing, material management, production, distribution to the last mile, returns and spare part management.

How did you arrive in this position?

After a brief spell with a healthcare company in the quality department- recommended for females in those days – I soon realized that I needed a greater challenge.

In 1996, I joined electrical device company, Hager. I wanted to start on the shop floor and I was given the task of automating the production line. It was a big project for my age but it gave me the chance to learn everything about indus- trialization and it gave me confidence to man- age people, even though they were not directly reporting to me. It was a three-year project at the end of which I was headhunted by Schindler to work on the industrialization of its main factory in Europe. I was later asked to move to purchas- ing and logistics, which was my first contact with supply chain and for which I first went for additional education.

Around 2000, we decided to collaborate with suppliers and innovate with what was available in the market. I was in this position for three years when, as regional supply chain representative, I was invited to a corporate group meeting. This was the beginning of our corporate purchasing organization and strategic sourcing, an idea originating from the Boston Consulting Group to leverage our cost position and further develop the supply base on a global scale.

Our ambition was to develop a manufacturing base in the Far East that could supply the entire world and simultaneously develop the Asian market for elevators which at that time was starting to boom. The supply chain of course also had to cope with this company ambition.

At the end of meeting, I was offered a job in corporate purchasing in Lucerne. In the end, I accepted and about a year later we moved to Switzerland. Luckily my husband and daughter were prepared to move too, even though we had just completed our new house in France! My function turned out to be much more than just strategic purchasing. We also set about optimizing the manufacturing footprint for the Schindler Group which involved much strate- gic discussion as we created a framework for suppliers.

And then you moved to the Far East?

I had been in that corporate position for four years and had had another child when my husband and I came to the conclusion that Switzerland was not the place we wanted to be for next ten years. We agreed that our next move would be based on who ever got the most interesting job opportunity first.

Schindler had a joint venture in China and I had been responsible for all the mechanics, the category management of doors and cars and afterwards for all mechanical parts. I had been travelling there quite regularly and felt comfortable there. I therefore decided to move with the family to China. However, even though it was the right moment for our family life, it was not the right time professionally. I was not successful in that job because I was not experienced or mature enough to get the project off the ground.

You made a decision, but it didn’t work out as you’d hoped. Did that impact yourconfidence?

Definitely! At first, I took it quite badly. I had built up a good reputation as someone with talent, someone to watch etc and now I was losing ground. I sat with my manager and I decided that I didn’t want to move out of Asia; if Schindler wanted me to go back to Europe then I would have to go somewhere else. My husband had the chance to move to Singapore so we moved there and I left the company.

It gave me time to think; Singapore is a small network and one of our Schindler suppliers, Sematic, approached me and asked about setting up a greenfield site in Asia. It was a small Italian family company that was willing to invest. I first became their consultant for 7-8 months, doing all the research I needed and came up with a business plan for opening a factory in China. They gave me the money to go ahead and we built the factory. We had an office in Hong Kong and I ran the company as COO. Within four years we broke even in China and developed the business. I wanted to prove to myself that I could do a greenfield site, even if it didn’t work out at Schindler!

It must have helped having the time to think and then working for a supplier?

Absolutely. I was very protected when I was at Schindler because I was part of an internal organization. The life cycle of a product is in the hands of many different departments and the destinies of the departments are linked. When you are a supplier you have to fight for a contract which doesn’t last forever. The life cycle of your product depends on your capability to stay competitive, be innovative, not only technically but also in managing and developing distribution networks. A lot rests on your capability to develop a good relationship with a manufacturer and make it feel dependent on you, even if it’s not. This was a very good learning experience and is something I’ve been able to use here so that everyone sees the value of supply chain.

How did you get commitment from the board for the transformation?

Optimization had been a topic for many years, even when I was here the first time. When you go through a transformation, you need to ensure that you don’t become too complex when you explain it. It needs to be very simple to ensure people don’t become scared because they don’t understand it. My concept of the single-entry point was written on one page, nothing very sophisticated.

You received the APICS Award for Excellence for spearheading the “Transform to Outperform” initiative that improved the com- pany’s operational performance. What was your approach?

In 2014, enhancing our service level, especially on-time delivery, quality and costs, was very challenging. These were my starting points. I used the SCOR model as a framework for end-to-end integration and went for the lean approach. My entire team, an internal organization of 152 people, was involved in the transformation. We held endless work- shops and went through months of number crunching. The main problem was the enormous complexity of bringing everyone together and getting information from both our suppliers and internal customers: our stakeholders and internal customers were very fragmented as every factory works independently and we deliver to branches in 55 countries. The issue in 2014 was that some internal customers did not see the value of supply chain as every factory and management organisation had and still has its own profit centre. Therefore we changed the business model to a single-entry point. This has given transparency to our internal customers. We are able to avoid duplication of cost and we have further improved the service level, quality and costs in the organization.

Did your colleagues enjoy this journey of transformation or has it been a struggle?

They enjoyed it because they were suddenly involved. It was adapted to their needs and they have been really part of it. We all had to dive in deep to get to the basic principles. However, the change management process first has to be in place and I sought help on this. You need to prepare people because you have different maturities, different levels of experience and different perceptions of change within the diverse disciplines. Knowing your people is very important.

How much time was spent on transformation, rather than day-to-day business?

We had 18 months of intense activities but we couldn’t just stop operations. Therefore, I didn’t want any major new projects even though we had 52 projects running at the same time. We categorized them in the work stream and marked the resources that were involved. Every month we looked at all of the projects and as soon as a project became too complex or overran we cut it. For example, one IT project became too big and would have jeopardized the rest, although we did use elements from it. The only exception was the single-entry point which took 18 months due to legal reasons.

Are elevators entering a new era, bearing in mind the level of urbanization and high-rise buildings, especially in Asia?

With innovations in our sector around digitalization, smart cities and traffic management, this can be described as a new era. Schindler is one of the leading players in these fields. We are facilitating the development of smart cities by focusing on mobil- ity around buildings such as offices, shopping centres and public transportation systems.

What is the next step for the Schindler supplychain? What are your next priorities?

For me it’s Industry 4.0, and how we manage and use digitally collected data. We need to use it for more than simply improving customer needs. We want to understand what we deliver, what data we can generate from the installation base in order to make us more agile in terms of spare parts availability, life cycle of components etc, and to understand where the supply chain net- work needs to be. We want our factories and machines to be part of a network rather than an individual location to improve actualization and capacity management. Because we do a lot of our own assembly, collaborative robotics, whereby repetitive activities are done by the robot with a person nearby doing value added activities, will be key. It is getting cheaper and cheaper and the ability to maintain agility, which was an issue in past with robotics, is improving.

How do you build in agility when the job to be done is changing?

A very important concept was to fully understand the value chain and where it can be less flexible. You can’t have agility everywhere at any cost so you have to cope with rigidity points and try to leverage them. You have to accept that this portion of your process means that a factory is not agile, not at all.

When you can visualize the rigidity point in the value chain you can front load as much as possible so this point becomes just a step, rather than a bottleneck. Your capability to anticipate is very important and it’s the reason why we put in place a process of S&OP to facilitate this front loading and create much more vis- ibility around it.

Is supply chain part of the R&D cycle?

No. R&D develops a standard solution with a platform for customization on a made-to-order basis. Sometimes the modification is minimal but it can be substantial. All buildings are differ- ent and the requirements, for example in Asia are quite different. Likewise, spare parts are not off the shelf, and are often commissioned. Obsoleteness is definitely a topic so we try to maintain a certain level of standardization, for example electronics, with a long life cycle. We own the software and have a very skilled organization that runs it.

Are you recruiting different kinds of people than a few years ago?

Yes, we hire more data analysts, although they are not easy to find and they are very different from traditional supply chain people. Whereas operational people see input-output, data analysts go beyond that: they think what we don’t yet see. Sometimes when they explain how implementing A will have an influence on B, people look at them as if to say what are you talking about. Their concept of data is also very different. Data for supply chain are usually figures that are presented in cells in excel files than can be used for activities with a function and turned into a graph and eventually a dashboard: data analysts don’t do excel files or dashboards because data is dynamic and a dashboard is static. They don’t talk about KPIs but instead how to get intelligence out of the data. It requires a completely different mindset. For some people, this is incomprehensible and that’s why people find it difficult to communicate with each other.

You are often presented as a role model for women in industrial manufacturing. How do you feel about that?

I was re-hired at Schindler because they know I’m a professional supply chain person. After nine months, they asked me if I would act as a role model, just to show what can be achieved in our industry. The supply chain has more to offer women than just purchasing. There are jobs available in the factory and in logistics etc.

Firstly, I believe it’s important to have women in such roles because otherwise the market may not take us seriously: it might question whether our company is sustainable if we are not open to opportunities in which diversity plays a part.

Secondly, our customer base has become increasingly diverse and, especially in Asia, the decision makers include more and more women.

And thirdly, we need more talent. It’s a waste if we only fish in half the talent pool.

What is your main message to our supply chain readers?

Before engaging in any transformation, consider what job has to be done: how can Supply Chain create value for my customers? If you don’t understand that, you won’t understand its value. The job to be done has to be done completely, not just for internal customers but also for their customers, the global contractors, and eventually the end customer. Once you know the job to be done, you then need to understand the difference between ‘the job to be done’ and ‘the job to be done today’. Then you start to connect, the transformation begins and you start to think about the next step.

For sure, you first use methodology to create a certain modularity because when you are in a complex supply chain you cannot touch everywhere with the same priority; you need a framework to understand where you need to act first. But it is not always the low hanging fruit. In my case the single-entry point was not the low hanging fruit but it needed to happen at the same time as the other activities.